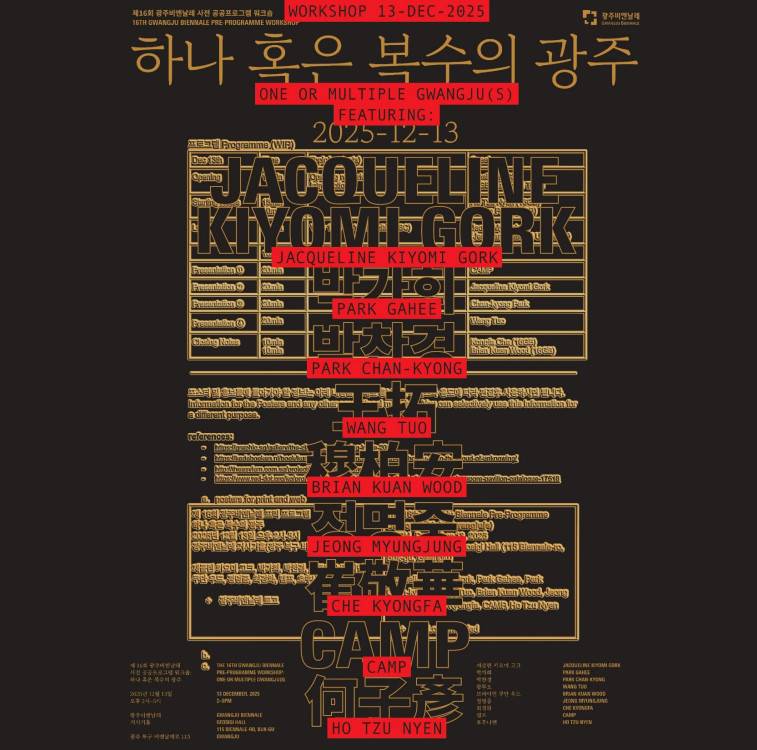

From the Category Video Art: Part II

July 27, 2008 - July 27, 2008

On the excess of images, and of access to images.

In this screening and discussion we look at several artist's works (including our own) based on security imaging or CCTV. This gives us a few new ways to think about contemporary images, and the "democracy" of image-making, in particular. It also suggests that the term "found footage" may not be sufficient, may even be misleading, for describing such work.

Saturday, July 26, 2008

(The screening schedule can be found by clicking on the tab above.)

If there are (by a rough count) some 3000 "security" cameras in the Bombay suburb of Bandra West where we live, what could this mean for practices of image-making?

In one way, it means nothing: these are images born into another world of the image, in which they then circulate, alone. They do not mix easily with other images, they are generally short-lived (the cheapest and most common CCTV systems don't record anything, and in the ones that do, images are being constantly overwritten, often by law). These image collections are then a continuously looping "backup": a bit like if we were recording TV all the time, in the hope that we will find something interesting in it, next week. Once in a while, a few images will indeed be pulled out as "evidence", or a video clip will leak out onto television or youtube. But these moments are brief, and their role is familiar. What is much stranger is that we live continuously in a Ghost City of images. This cloud taps us gently on the shoulder as we move about, but its own full reality or depth is something we are unable to grasp.

The (eco)system of video as a security "medium" creates, and actually is founded upon, a vast material excess. This surplus is not only in the sense that these images exceed language, commodity and so on, but also that in a very physical way, these are a lot of images. Yet their ghostly mass appears to lie beyond simple notions of the extraction of utility or value from it. (For example it often acts outside of itself, as a "deterrent", or as a body-in-waiting for an event that never actually happens.) We could say that this hidden material possesses "abuse-value" - a taking without giving, a one-way utility that precedes other forms of value. [1]

Now, a glut in the images folder is not unfamiliar to contemporary image-makers. Filmmakers and photographers working "digitally" are quite aware that ours is a materially excessive practice, even compared to a few years ago. There is a growing "digital divide" between the shots that have been "taken", and those that may eventually resurface as films, exhibitions, online or in any other form. We are realising also that this abundance is not "free", there is a lot of cameras, tapes, hard-drives, storage space and time being spent on it. But this will not slow us down. So what are the real and psychic dimensions of this excessiveness? What is happening as we gather things we cannot possibly use? Put differently, what is happening as we collectively wait, for the on-camera event that will justify the expense, and sate our current curiosities? On the one hand this is a space of potential, the reverse side of production. But it is also the dark side of the "democratisation" of video, and "access" to its tools, claimed in so many places since the 90's. The waiting game is most effectively seen in Indian television today: in all those cameras ready to pounce upon the shadow of an event, and the ultimate in money-shot camera-tricks, the sting operation. The use of such imaging is justified always by good intentions, and "greater concerns" of the "public". But this is the language of the police, and so the search for even better justifications, even nobler intentions in the realm of professional imaging, is perhaps the wrong one.

If we can temporarily suspend the good intentions and diverse subject positions of various agents "making films", producing image-narratives and so on, we have some more options: we could propose for example that video is a substance, a bit like electricity or water, or like refrigeration or LPG, or like a fog or sewage, in the urban bloodstream. Now if water produces a number of chemical solutions and cleansing rites, if electricity leads to communism or to "Shakti-Anantam" (depending on if you follow Lenin or Modi), and if LPG is at the heart of food, the national oil policy, and cylinder-bombs... where exactly does such video lead us? Does it lead the way to "understanding", "safety", "our voices" or "voyeurism"? This is not a "modernist" deterministic question, it is a question for the democracy of images. Is it merely inevitable that everyone will watch everyone else? What happens next? How can we distinguish images used by the police from the ones offered in friendship? How do we recognise "abuse-value"? The only way perhaps is to go deeper into the conditions in which video is made, with or without human intention, with or without our consent. This is where security video may lead the way, because it has already entered into such material territory, and into various still-debated positions of the subject. Moreover, it may allow the time, more than any other form, to ponder all of these questions. Closer to the ground into which such video is embedded, we see "secondary" effects: what is being redistributed here is not only views or watching power, but a gradual realignment of abilities and senses... not all of which are well understood, or can be accounted for by the term "surveillance" or its counter-theories (exhibitionism, sousveillance, and so on).

In the case of the bandra shopkeepers for example, the CCTV system appears to be a form of inattentive TV-watching. But it is also psychically linked to older constructions of glass and mirrors; entire architectures by which corners would be turned, employees watched, goods doubled, glimpses stolen of the clouds and of the traffic outside... all the while carefully avoiding the traumatic geometry (for the shopkeeper) of having to look at oneself in a mirror all day. Interior designers know this... but who knows the genetic effects of a couple of generations of mirror watching, or being watched? In what ways do these images now enter the mindscape of professional waiting, what spaces of reflection are now opened up, what dreams or nightmares could follow?

At the other end of the stick, as it were, in the control rooms of large CCTV systems there are other lineages, other openings. Working-class operators train to be "cameramen", learn framing and following techniques, turn into habit the legally-defined limits of zooming in and zooming out. They watch people and neighborhoods that become increasingly familiar, at a distance. Over time, this becomes mechanical and lonely, but this is also a loneliness continuously expecting, seeking, the Big Event: a breakdown in the social world one has "left" outside, an overflow of the simultaneous enjoyments of voyeurism and duty.

In such infrastructures then, just as when other technologies become settled or pervasive, the ability to act and to produce meaning (what is called "agency"), has shifted from the old places, has become intertwined with changing technology and context, has changed size or shape. Where has it gone to? What does it look like? The videos presented here attempt to answer these questions, through the work of artists who have engaged with this "medium" for some time.

These are artists going hard at images, a quite different idea from the artist as a person "taking the picture", "making the picture", or even "assembling" a picture. This work attempts to simultaneously challenge and produce the conditions in which such a picture can be "taken" (ingested, assimilated, revealed). It is here a question of disrupting the order of images, in order to produce one's own.

“Found footage” can now be seen as a somewhat quaint term. It is obvious that such footage is not "found", as if somehow lying on the road, but is actively sought out, negotiated, stolen, bought, and so on. If the term "found footage" came from art history's found-objects, or objet-trouve, it appears today that footage-objects are part of a much more protected domain of material life, in which they must be extracted from regimes of the not-for-your-eyes, borrowed from the "belongings" of someone else, and then purified, sexualized, exposed, re-buried, suspended, replayed or dispersed anew.

For us (CAMP) this approach is related to ongoing work around technical infrastructures. The work with video is an attempt to open up a space, in our context, outside of documentary films, television or popular cinema as the default triumvirate of sites for both the production and understanding of images, as "father figures" for all other moving-images. The point is not so much that CCTV video will enter into the art world (as it has) or that there will be Bollywood films shot with it (there are, and there will be more), but that strategic traversals of these fields can create an energy, a politics. It may be eventually that the non-overlap, or lack of commonality, of security images with more traditional ones is what needs to be sustained, to render "inoperable" (in Jean-Luc Nancy's sense of a community based on unharmony) our growing community of images.

The ongoing series around Video Art is similarly an attempt to tease apart these two words, to expand the category they enclose, to populate the boundaries of what a video art can be.

(p.s. the artists here don't necessarily share our views on the above. As before, the majority of these works are found online, there is one exception.)

Notes:

(1) Abuse-value has been used in atleast two different contexts: by Michel Serres in writing about "parasitic" abuse value, as an "arrow with only one direction", a taking without giving back. This can also have its positive, or fortunate side. And by Arthur Kroker and Michael Weinstein more negatively as the "last" value that may be extracted from the weak and oppressed. Here it is used more in Serres' sense.

Screening Schedule

I Thought I was Seeing Convicts

Harun Farocki (2000)

25 mins

The film borrows its title from a dialogue in a Rossellini film, Europa 51, where Irene (Ingrid Bergman) a wealthy lady, goes to work in a factory for a day to find it like a prison. Here, as you watch prisoners meet their loved ones, or get set up in a 'playground' for a fight, the surveillance visuals become images that allow for a perverse humanisation of the prisoners, just as you are reminded that in this space the field of vision and the field of fire literally coincide.

The Great Indian School Show

Avinash Deshpande (2005)

Excerpt: 20 mins.

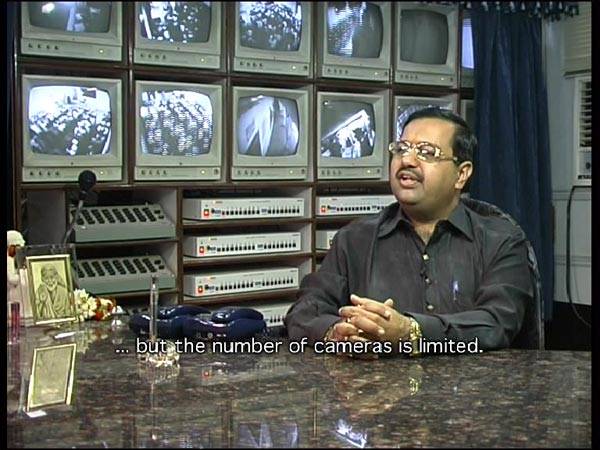

Excerpts from Deshpande's film, which not only allegorises control as a requisite for new nation building, replacing the state with private law and discipline, but also because it shows us one logical extreme of the 'democratic' access to technology. This is the story of Mahatma Gandhi High School in Nagpur, which had installed 185 security cameras, with the principal's chamber as the control room.

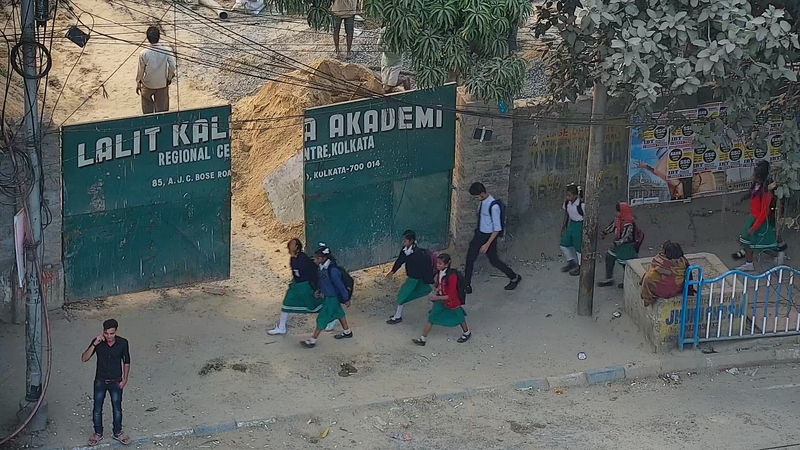

Scenes from the Neighbourhood: Neelam, Royal, China Gate, et tu Janta?

CAMP (2008)

5 mins.

Glimpses of CAMP work with security video in new "settings" in our neighbourhood.

Khirkeeyaan

Shaina Anand (2006)

Excerpt 10 mins.

Khirkeeyaan achieves a radical inversion of CCTV's apparatus: cameras and mikes are cross-linked through a standard CCTV box, to create a conversational space using household TV's. A number of different installations or "episodes" in Khirkee village, Delhi were staged, ranging from an onscreen meeting of Nepali household help and the landed elite's "bahuraniyan", to a doctor giving dubious advice, to barber shops and political debate, to four basement factories and their workers being exposed to each other.

CCTV Social:Clinic and Regeneration.

Shaina Anand (2008)

excerpts 15 mins

In March 2008, Shaina Anand's project opened CCTV control rooms in Manchester to members of the general public, who signed up for one hour "therapy" sessions. About 40 people spent an hour each in control rooms where Manchester's Open Street Surveillance was in action. In the Arndale, one of Europe's largest malls and the site of the 1996 IRA bombing that "saved Manchester" (by kick-starting its regeneration program) about a hundred people signed image-realease forms, to allow their images from the 206 cameras in the mall to be used, for a film that is under production.

Faceless: Spectral Children

Manu Luksch (2006)

15 mins.

FACELESS was produced under the rules of the 'Manifesto for CCTV Filmmakers'. The manifesto states, amongst other things, that additional cameras are not permitted at filming locations, as omnipresent video surveillance is already in operation. Filmmaker Manu Luksch exploited a clause in the UK Data protection act that allowed an individual access to their own footage from the Operating agency, for a processing fee of £10. The Privacy law demanded that all other indentifiable people in the visuals had to be blacked out or blurred. After copious exchanges over several years, Luksch had "recovered" enough footage of herself and other actors to create Faceless, a sci-fi fairy tale about a world where everyone lives in real-time, without memories...Spectral Children is a shorter installation version.

Video Sniffing.

Mediashed (2007)

Excerpt 5 mins.

Capturing the images of of a CCTV system from outside it, and some performances around this practice.

Evidence Locker: Trust

Jill Magid (2005)

15 mins.

Instead of portraying the civilian as hapless victim of state surveillance, Magid's works attempt reversals by drawing the observers/police into personal relationships, flirtations, unexpected intimacies. In Evidence Locker, she successfully tweaks the function of Liverpool's city-wide surveillance system (the largest of its kind in England) by having the operators follow her around as she got to know them. For access to this footage, Magid had to submit 31 Subject Access Request Forms, which she wrote as though they were letters to a lover, expressing how she was feeling and what she was thinking. In the video Trust, Magid on the phone, eyes tightly closed, asks the CCTV operator to guide her through a busy city street.

Nightwatch

Francis Alys (2004)

15 mins.

One night in 2004, Alys set loose a fox inside the National Portrait Gallery in London, and filmed the results using the gallery's security system.